Before the United States entered World War II, the few women working at the Brooklyn Navy Yard did traditionally “female” jobs. They sewed flags, or filled clerical or administrative positions. But when men went off to war after Pearl Harbor, women stepped up to become, not only riveters like Rosie, but also welders, shipfitters, and mechanics. This week, a few words and pictures about women’s wartime role, and what those new possibilities for women had to do with my fictional characters, my real-life family—and last week’s spectacular rocket launch.

Women sew flags at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, 1909.

When I saw a copy of Life Magazine from February 23, 1942 on eBay, I jumped on it. It arrived a few days later, and I eased it out of its cellophane envelope and stepped into a time machine—back three quarters of a century to a fraught period when the United States was ten weeks into World War II. That war would upend, at least for a while, America’s notions of a woman’s place in the world.

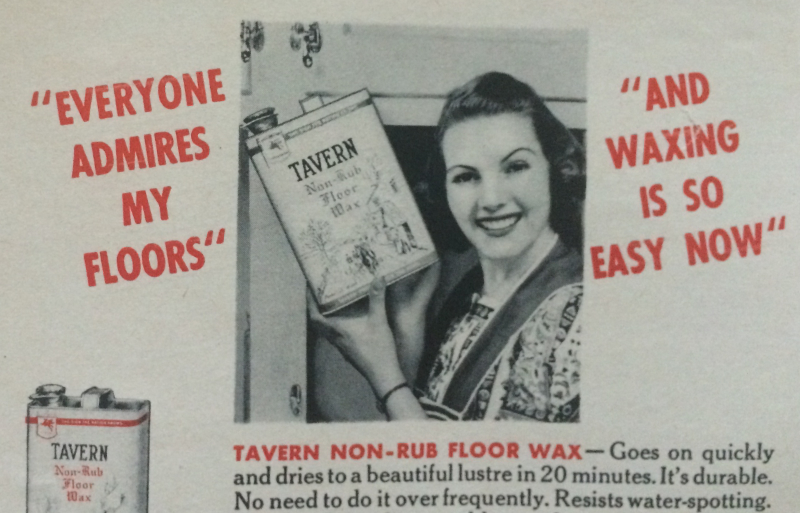

The magazine is chock-full of advertisements that depict women working blissfully at their domestic duties with the aid of the latest appliances and products. Those images reflect the prewar feeling that the work of the “girls” was to stay home and take care of their husbands and children.

“Waxing is so easy now.” Floor wax ad from Life Magazine, February 23, 1942.

With a fine Maytag like this one, what’s not to smile about? Ad from Life Magazine, February 23, 1942.

On the BLDG 92 blog, we can read about men’s initial skepticism toward women doing “men’s work,” and their eventual acceptance of it. “It is a big jump from carpet sweeping to electric welding,” says an article in the Shipbuilder in November, 1942, “from the noise of a vacuum cleaner to that of a hundred riveters pounding on great steel bulkheads.”

But, the article goes on to say, “What [skeptics] failed to count on was the spirit of American women, which is the spirit of America itself. This was the invisible bridge across the gap between the old occupations and the new.”

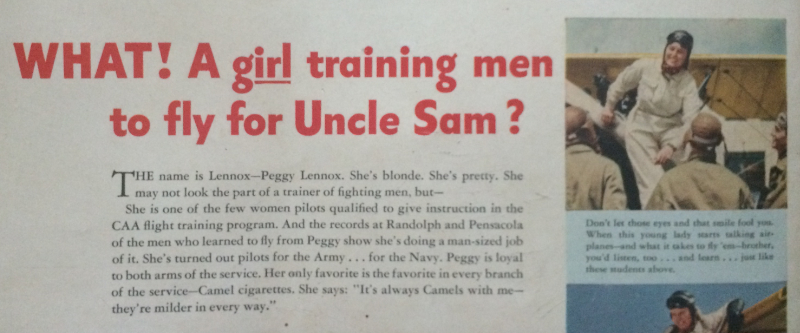

So, yes, thousands of women built and repaired ships during World War II. Of necessity, society started to accept new roles for women. The advertising in my old issue of Life reflects some of that new attitude, as well. Here’s the back cover:

In the same issue of Life Magazine, a “girl” who teaches men to fly.

If you’ve read Part 1 of my Can-Do Yard posts, you’ve probably guessed that the fictional great-grandparents in my work in progress illustrate this narrative. Seamus went off to defend freedom on the high seas, and Rose became a welder at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Her own father, a descendant of famine Irish, grew up shoeing horses and forging wagon wheels in New York’s Hudson Valley. Ironworking was in Rose’s blood, and steel was in her spine. Then the war ended, and Rose retreated to more womanly pursuits.

Or did she?

You can listen to some gutsy real-life women, women a lot like the fictional Rose, talking here about their own experiences doing “men’s work” at the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

In 1909, long before women took up their acetylene torches, my grandmother stood at the railing of the U.S.S. Columbia (2) as it steamed into New York Harbor. When the Statue of Liberty came into view above the shining water, she knew that, in America, a woman could achieve anything. Two generations later, when her first granddaughter was born, she marveled that this tiny baby could grow up to be an engineer and work at General Electric—”The GE,” as it was known locally.

I thought about that last week, when SpaceX successfully launched and landed the Falcon Heavy. What an amazing feat—I was cheering along with everyone else, including the roomful of engineers so deservedly celebrating their achievement. But you can’t help but notice the thing that soon lit up Twitter: those engineers are almost all men.

Of course there are female engineers, including at SpaceX, but tech fields are notorious for being disproportionately male. Gwynne Shotwell, president and CEO of SpaceX, quoted Bella Abzug at the 33rd Space Symposium last year: “Our struggle today is not to have a female Einstein get appointed as an assistant professor. It is for a woman schlemiel to get as quickly promoted as a male schlemiel.”

Achieving the same employment opportunities as male shlemiels doesn’t seem like too much for women to ask. Sadly, though, even this modest hope still feels far out of reach.

I think I’ll ask my grandma to go haunt some tech executives.

Engineers celebrating SpaceX test flight.

My current work in progress, We Still Have Us, tells the story of a seventeen-year-old girl in upstate New York who’s caught between poverty and privilege, dreams and duty, past and future. You can read more about it here. And for writerly updates, news, and commentary, subscribe below to my newsletter.