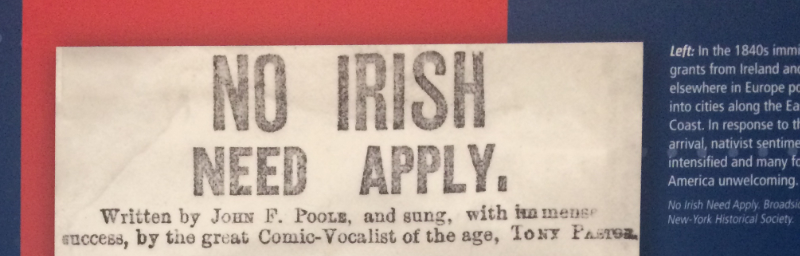

At the Navy Yard museum in Building 92 on Flushing Avenue, Brooklyn, you can read the lyrics to a popular song of yesteryear: “No Irish Need Apply.” I don’t remember encountering much anti-Irish sentiment in my life—lucky me—but it still stung me to see that exhibit, and not only because I feel connected to my own departed ancestors. I’m also attached to my fictional characters, and my tour of the Navy Yard last fall made me appreciate them even more. This post is not about the Navy Yard, but it was inspired by my visit.

Exhibit at museum at Brooklyn Navy Yard: “No Irish Need Apply” song.

I’ll take whiskey, myself (spelled the Irish way, with an ‘e’), but when Famine Irish poured out of Ireland and landed in New York, a coded language arose to exclude them from job postings.

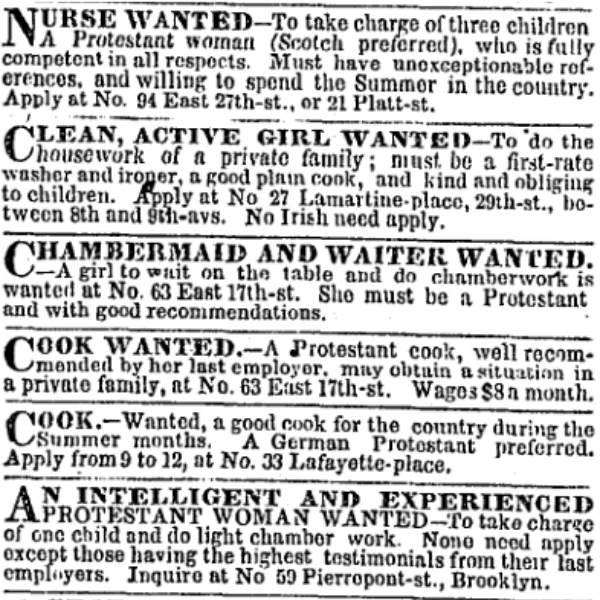

“Scotch preferred.” “A Protestant woman.” “German.” “German Protestant.” “A Protestant cook.” Most of the Famine Irish were Catholic, so these stipulations can all be read as code for “No Irish Need Apply.” The phrase is often abbreviated as NINA, or sometimes turned around as INNA (“Irish Need Not Apply”).

But Irish did apply, in droves. What else could they do? Many had disembarked in New York malnourished, sick, and too poor even to fan out across their new land. Instead, they stayed put in the city. Some took a ferry from Manhattan to Brooklyn (there was no Brooklyn Bridge, because the Irish, and other immigrants, hadn’t built it yet) and settled along a long swath of the borough’s waterfront. Having little choice but to work for desperation wages, the men labored at factories, construction sites, and docks, building the New York we know today. The women cooked and cleaned for wealthy families.

In 2002, a university professor published a scholarly paper called “No Irish Need Apply: A Myth of Victimization.” In it, he argued that actual, physical signs placed at physical businesses and meant to discourage Irish men from applying simply did not exist, and that “[a]part from want ads for personal household workers, the NINA slogan has not turned up in the newspapers.”

Where shall I begin?

Classified ads in the New York Times archives. All say, overtly or in coded language, that no Irish need apply.

Let’s leave aside those want ads for the moment. The professor doesn’t deny that they existed; he merely minimizes their significance. No, his thesis is that actual, physical signs advising Irish men they need not apply for work were very rare—so rare that not even one has endured. To be sure, he says, “elderly relatives” insist the signs were real. But those people are elderly; he views their memories as not oral history, but urban legend, implanted by too much exposure to that song I mentioned above. Possibly, he suggests, “after a few rounds of singing and drinking,” the signs became visible to the inebriated Irish.

So the argument he’s making is that, since he didn’t find physical evidence of such signs, it’s unlikely they existed. I don’t buy it. Getting back to my food analogy above, isn’t that kind of like saying that, since not a single bowl of mutton stew from those days has ever been found—not one!—mutton stew must not have existed? That, more likely, it appeared like a vision dancing in front of people’s eyes after they’d consumed a few pints?

And never mind statements from no lesser personages than the late Tip O’Neill, former Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, and the late Ted Kennedy, former U.S. Senator from Massachusetts, that they had seen such signs themselves. The professor writes that “reports of sightings in the 1920s or 1930s suggest the myth had become so deeply rooted in Irish-American folk mythology that it was impervious to evidence.”

Oh, those Irish-Americans. Such a simple folk.

But doesn’t it also strain credulity that hiring discrimination should have been restricted to “only” those classified ads aimed mainly at women? If female Irish immigrants were unwanted, does it seem plausible that male Irish immigrants would have been hired without prejudice? That doesn’t make sense to me.

It didn’t make sense to eighth-grader Rebecca Fried, either. More than a dozen years after the original paper appeared, she offered a rebuttal that was published in the Oxford Journal of Social History on July 4, 2015. Although the 2002 “Myth” article seems to have attracted little attention when it was first printed, Rebecca’s response stirred the pot. All hell broke loose. Go ahead and Google it. You’ll see that feelings are still running high.

To be honest, I’m not sure how common those signs were. I’m not a historian, and I don’t have the research skills to do a scholarly study of the subject. A lot of so-called “evidence” gets quoted and requoted in the internet hall of mirrors.

What’s not in doubt is that the Irish experienced hardship and discrimination when they first arrived—like so many waves of immigrants before them, and since. It took generations, and bushels of grit, to overcome the challenges of their hardscrabble existence. Not all of my forebears were Irish, but they were all immigrants, and I’m proud of them. I’m inspired by their story. I’m glad they stuck it out, and raised up future generations of Americans.

As I mentioned in last week’s post, the great-grandparents in We Still Have Us have history in New York City. They will have faced all sorts of challenges as they tried to make their way in their new country, and I’m interested in understanding those challenges. I can see all sorts of adventures for these characters. One may help build the Erie Canal; another, the Brooklyn Bridge. Yet another may enlist in the Navy and serve in World War II. Women can become union organizers (remember Mary Harris “Mother” Jones?), or suffragettes. So many possibilities! And none of those experiences will unfold without conflict. That would just be boring 😉

My grandmother, who immigrated to America in 1909 at the age of eighteen, was a Protestant Englishwoman with an English surname.

Except she wasn’t. In reality, she was a sixteen-year-old Irish Catholic with an Irish surname that she changed before getting onto the ship to come here. By claiming to be eighteen, she was able to come here unaccompanied. By claiming to be Protestant, she could circumvent anti-Irish, anti-Catholic prejudice. The large family she left behind sent her to a new land so she could get an education. Later documents show she eventually changed her first name, too. How do I know this? Because she told her daughter—my mother.

Why did she change her identity before leaving Ireland? Because, she told my mother, she didn’t want everyone in New York to think of her as an “Irish washerwoman.” She wanted something better for her new life. Respect. Dignity. A fair shake.

My maternal grandparents, Hannah and Roy.

Was my grandma being disloyal to her roots? I don’t know; I never stood in her shoes. My fate didn’t involve having to leave my homeland and my entire family in search of a better future. When I went looking for my first job, I wasn’t disadvantaged merely by my religion and country of origin.

I do know I’m glad I learned some part of the truth, even if there is still so much more to learn. The written record offers little in the way of concrete evidence—but it’s a principle of research that where the archives are silent, there must be silencing.

Only a deep dive into immigration records by my sister finally turned up vital clues. She found my grandmother’s Irish first name and English last name on the manifest of a ship whose route included a stop at Moville—a popular embarkation point for Irish travelers. Additional records show that this same passenger was immediately sent to the hospital upon arrival, and was released two weeks later to the care of an auntie. The auntie’s particulars could be matched up to known family history.

It took time, money, and dedication to find this information. It would have been easy to conclude that no evidence existed. But because someone told someone, who told someone else, there was a kernel to start from. The fact that the initial kernel for the search came from an oral history starting with my grandmother and passing down through my mother to us does not make me want to dismiss it as a myth, alcohol-fueled hallucination, or urban legend.

Not even close.

My current work in progress, We Still Have Us, tells the story of a seventeen-year-old girl in upstate New York who’s caught between poverty and privilege, dreams and duty, past and future. You can read more about it here. And for writerly updates, news, and commentary, subscribe below to my newsletter.